As I stated in my previous article timers are hard to use the right way so here are some handful tips.

Edit (16 Dec 2024)

This post is still here for historical reasons, but it’s now quite old.

Many of the issues in this post have been corrected and some footguns don’t hold true anymore.

Please consider this as a window into a “previous Go experience” and nothing more.

As a general approach always refer to upstream documentation when looking for insights on Go.

Preface

If you don’t think dealing with time and timers while also juggling goroutines is hard, here are some juicy bugs related to time.Timer:

- time: Timer.Reset is not possible to use correctly #14038

- time: Timer.C can still trigger even after Timer.Reset is called #11513

- time: document proper usage of Timer.Stop #14383

If you are not satisfied, in the following code there are a deadlock and a race condition:

tm := time.NewTimer(1)

tm.Reset(100 * time.Millisecond)

<-tm.C

if !tm.Stop() {

<-tm.C

}This just has a deadlock:

func toChanTimed(t *time.Timer, ch chan int) {

t.Reset(1 * time.Second)

defer func() {

if !t.Stop() {

<-t.C

}

}()

select {

case ch <- 42:

case <-t.C:

}

}That said, let’s get to the tips.

time.Ticker

type Ticker struct {

C <-chan Time // The channel on which the ticks are delivered.

}Ticker is quite easy to use, with some minor caveats:

- Sends will drop all unread values if

Calready has one message in it. - It must be stopped: the GC will not collect it otherwise.

- Setting

Cis useless: messages will still be sent on the original channel.

time.Tick

This is just something you should never use unless you plan to carry the returned chan around and keep using it for the entire lifetime of the program.

As the documentation states:

the underlying Ticker cannot be recovered by the garbage collector; it “leaks”.

Please use this with caution and in case of doubt use Ticker instead.

time.After

This is basically the same concept of Tick but instead of hiding a Ticker, hides a Timer. This is slightly better because once the timer will fire, it will be collected. Please note that timers use 1-buffered channels, so they can fire even if no one is receiving.

As above, if you care about performance and you want to be able to cancel the call, you should not use After.

time.Timer (also known as time.WhatTheFork?!)

I find this to be quite an odd and unusual API for Go: NewTicker(Duration) returns a *Timer, which has an exported chan field called C that is the interesting value for the caller.This is odd in Ticker, but very odd in Timer.

Usually in Go exported fields mean that the user can both get and set them, while here setting C doesn’t mean anything. It’s quite the opposite: setting C and resetting the Timer will still make the runtime send messages in the channel that was previously in C.

This is even worsened by the fact that the Timer returned by AfterFunc does not use C at all.

That said, Timer has a lot more interesting oddities. Here is an overview on the API:

type Timer struct {

C <-chan Time

}

func AfterFunc(d Duration, f func()) *Timer

func NewTimer(d Duration) *Timer

func (*Timer) Stop(bool)

func (*Timer) Reset(d Duration) boolFour very simple functions, two of which are constructors, what could possibly go wrong?

time.AfterFunc

Official doc: AfterFunc waits for the duration to elapse and then calls f in its own goroutine. It returns a Timer that can be used to cancel the call using its Stop method.

While this is correct, be careful: when calling Stop, if false is returned, it means that stopping failed and the function was already started. This does not say anything about that function having returned, for that you need to add some manual coordination:

done := make(chan struct{})

f := func() {

doStuff()

close(done)

}

t := time.AfterFunc(1*time.Second, f)

if !t.Stop() {

<-done

}This is stated in Stop documentation.

In addition to that, the returned timer will not fire. It is only usable to call Stop.

t := time.AfterFunc(1*time.Second, func() {

fmt.Println("Time has passed!")

})

// This will deadlock.

<-t.CAlso, at the moment of writing, resetting the timer makes the runtime call f again after the passed duration, but it is not documented so it might change in the future.

time.NewTimer

Official doc: NewTimer creates a new Timer that will send the current time on its channel after at least duration d.

This means that there is no way to construct a valid Timer without starting it. If you need to construct one for future re-use, you either do it lazily or you have to create and stop it, which can be done with this code:

t := time.NewTimer(0)

if !t.Stop() {

<-t.C

}You have to read from the channel. If the timer fired between the New and the Stop calls and the channels is not drained there will be a value in C, so all future reads will be wrong.

(*time.Timer).Stop

Stop prevents the Timer from firing. It returns true if the call stops the timer, false if the timer has already expired or been stopped.

The “or” in the sentence above is very important. All examples for Stop in the doc show this snippet:

if !t.Stop() {

<-t.C

}The problem is that “or” means that this pattern is valid 0 or 1 times. It is not valid if someone else already drained the channel, and it is not valid to do this multiple times without calling Reset in between. This summarized means that Stop+drain is safe to do if and only if no reads from the channel have been performed, including ones caused by other drains.

All this is stated in the doc by the sentence below:

For example, assuming the program has not received from t.C already:

Moreover, the pattern above is not thread safe, as the value returned by Stop might already be stale when draining the channel is attempted, and this would cause a deadlock as two goroutines would try to drain C.

(*time.Timer).Reset

This is even more interesting. The documentation is quite long, and you can find it here.

One funny extract is:

Note that it is not possible to use Reset’s return value correctly, as there is a race condition between draining the channel and the new timer expiring. Reset should always be invoked on stopped or expired channels

The doc says the right way to use Reset is the following one:

if !t.Stop() {

<-t.C

}

t.Reset(d)You cannot use Stop nor Reset concurrently with other receives from the channel, and in order for the value sent on C to be valid, C should be drained exactly once before each Reset.

Resetting a timer without draining it will make the runtime drop the value, as C is of size 1 and the runtime performs a lossy send on it.

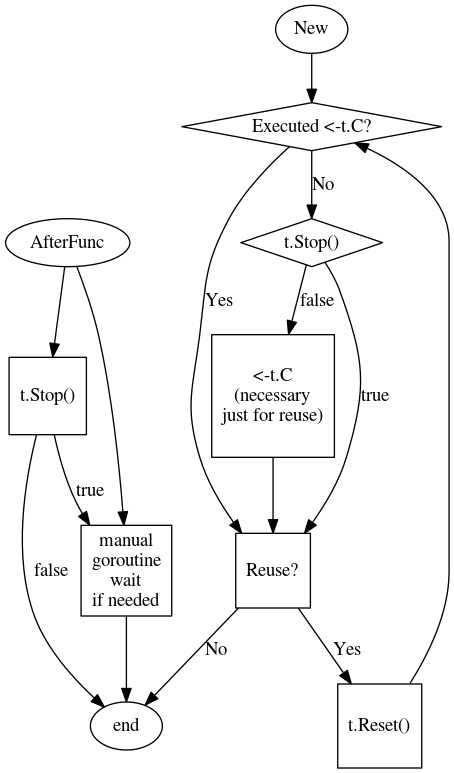

time.Timer: putting it together

Stopis safe only afterNewandReset.Resetis only valid afterStop.- Received value is valid only if channel is drained after each

Stop. - The channel should be drained if and only if the channel has not been read yet.

Here is a flowchart of the allowed transitions, uses and calls on a timer:

An example of a correct re-usage for a timer, which fixes one of the trivia at the beginning of this post:

func toChanTimed(t *time.Timer, ch chan int) {

t.Reset(1 * time.Second)

// No defer, as we don't know which

// case will be selected

select {

case ch <- 42:

case <-t.C:

// C is drained, early return

return

}

// We still need to check the return value

// of Stop, because t could have fired

// between the send on ch and this line.

if !t.Stop() {

<-t.C

}

}This ensures the timer is ready to be re-used after toChanTimed returns.

Want to know more?

All types and functions described in this post rely on runtime timers, they just use it differently. time/sleep.go contains most of the code using them.

Here is a table with fields of runtimeTimer set by the time package:

| Constructor | when |

period |

f |

arg |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NewTicker(d) | d |

set to d |

sendTime |

C |

| NewTimer(d) | d |

not set | sendTime |

C |

| AfterFunc(d,f) | d |

not set | goFunc |

f |

Runtime timers do not rely on goroutines and are bucketed together to fire in an efficient and precise manner. In runtime/time.go you can start digging into the actual implementation. Have fun!